How the AI Race Is Revitalizing the Asian American Dream

By Romen Basu Borsellino | 05 Sep, 2025

The ferocious US demand for AI-trained talent is amplifying opportunities for Asian immigrants even as more traditional tech talent is set to undergo a major shakeout.

Imagine setting out to build a Super Bowl-winning football team.

As the team’s owner, you’ve got nearly every piece in place: The best plays ever drawn up. The greatest coaches. The most state of the art football field and practice facilities and the greatest equipment ever constructed including helmets, pads, even footballs deflated to Tom Brady’s preferred PSI.

But what you don’t have are the players. At least, not a full roster. Not yet.

Super coders in their twenties are being offered extravagant sums of money to develop AI for top tech companies

This is, to a very simplified degree, the current situation that the United States finds itself in with regard to the AI race. And it’s one that our leaders are practically declaring an existential fight for survival.

There’s a reason that, say, Nvidia, the top creator of AI processors and related software libraries, is the world’s most valuable company by market cap.

But today every tech giant — Meta, Alphabet, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon — has made a hard pivot to developing the world’s best AI large-language models (LLMs) with which to sell AI cloud processing capabilities to just about every person on the the planet.

As it turns out, these AI aspirants find themselves doing exactly what most sports franchises find themselves doing: shelling out the big bucks.

As the New York Times recently wrote, “Silicon Valley’s A.I. talent wars have become so frenzied — and so outlandish — that they increasingly resemble the stratospheric market for N.B.A. stars.”

But unlike professional athletes, the world’s top AI experts happen to be mostly Asian.

The $$$

Mark Zuckerberg has outbid other tech giants by offering upwards of $1 billion in total compensation for top talent who are mostly from China which has been leading the world in training talent capable of developing world-class AI technology

Per a piece in the Wall Street Journal, titled “These AI-Skilled 20-Somethings Are Making Hundreds of Thousands a Year,” recent college grads who understand AI are making base salaries of $200,000.

And then there’s the position of “super coder.” These are the people who are truly on the front lines of the AI revolution and earn salaries that make $200,000/year look like pocket change. As the New York Times has noted, “Only a small pool of people have the technical know-how and experience to work on advanced artificial intelligence systems.” These folks comprise that small pool.

The Times recounts Mark Zuckerberg recently offering a 24 year-old AI researcher $250 million over four years. It’s legitimately hard to wrap one’s head around these sums of money. Then again, the work they're doing is even harder to comprehend.

And where do these super coders come from?

Asia, it turns out.

Talent

President Trump recently told China's President Xi that he would be "honored" to allow twice the number of Chinese students that are currently in the US

Asia appears to have developed monopolies in training talent capable of developing world-class AI technology.

This is due at least partially to the dense populations of those countries, and therefore raw numbers of qualified candidates that they’re able to produce. There are between 600,000 and 700,000 graduates in STEM fields in the US each year. China and India, on the other hand, produce 4 million and 2.6 million STEM graduates a year, respectively.

And it’s not just raw numbers but percentages as well. About 20% of US grads are in STEM. In China, that number is 30-35%.

Former presidential hopeful and current Ohio gubernatorial frontrunner Vivek Ramaswamy made headlines for posing a theory on Twitter late last year about why that is:

The reason top tech companies often hire foreign-born & first-generation engineers over “native” Americans isn’t because of an innate American IQ deficit (a lazy & wrong explanation). A key part of it comes down to the c-word: culture.

The cultural difference, in Ramaswamy’s view, is that Asians value nerdiness over coolness. They put a premium on, say, mathletes while the US gives more social status to the prom queen or football quarterback.

Whether or not you agree with Ramaswamy’s underlying diagnosis for Asian supremacy in producing STEM talent, it is undeniable that countries like China and India are simply producing more students and recent graduates with the skills that AI software companies need.

One alternative explanation — or perhaps, a direct result of that cultural difference — is explained by the sheer number of schools in Asia that offer a STEM education.

Ramaswamy also caught flack from members of his own party when it came to his solution, aside from changing the culture: granting more H-1B visas to those who have the skills.

But even those in his own Republican party — which is known for its hardline anti-immigration stance — may have come to the conclusion by now that there’s virtually no way around granting entry to a greater number of foreigners with the skills our AI companies require.

President Trump himself appears to have reached that conclusion. After months of threatening to revoke the visas of Chinese students, he’s struck a deal with China to admit 600,000 Chinese students to the US over the next two years.

This is a win for Asian Americans.

The move has angered members of Trump’s own base, like Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, celebrated by the MAGA base by elevating xenophobia to operatic scales.

And, yet, her concerns are likely born out of the same reasons that Asian Americans should be celebrating this news: the admittance of more Asian students will be a boon to Asian American culture. It’s likely to breed more Asian restaurants, entertainment and cultural districts.

This is just one way in which the rise of AI is a win for the AAPI community.

The Missing Pieces

If China is leaps and bounds ahead of the US in terms of talent, one might wonder why they haven’t gone full Usain Bolt and pulled ahead in the AI race already.

It’s because a football team that simply consists of Patrick Mahomes standing alone in the middle of a field is no football team. Talent needs to go hand in hand with the other moving parts required to fabricate the millions of high-powered, high-bandwidth graphic processing units (GPUs) to fill hundreds of giant data centers.

When it comes to producing that type of design and fabrication technology — developed painstakingly over the past 70 years of the computer age — China simply hasn’t been in the game long enough to match the US and its close allies like Taiwan, S. Korea, Japan and the Netherlands.

Their capabilities may be good, but at this level, good isn’t…well, good enough. It needs to be great —nay, perfect.

Any Breaking Bad fan surely remembers chemist-turned-drug kingpink Walter White’s fixation on the purity of the crystal meth he’s making: “You produce a meth that's 70% pure, if you're lucky. What I produce is 99.1% pure,” he says to his competitor. “Yours is just some tepid, off-brand, generic cola. What I'm making is classic Coke."

When it comes to the ability to churn out GPUs, the US and its allies are currently the Coke to China’s generic cola, although theirs is probably closer to 40% “pure” than 70%. In meth terms, to keep going with this Breaking Bad analogy: it can still get you high, you just need to buy 2-3x more of it. Which is to say that while China is nipping at our heels in terms of developing AI models, their ability to make the hardware to power them is perhaps three to five years behind. And given the pace at which the world is addicting to AI, those years may as well be dog years.

Still, China is catching up with the manufacturing hardware and infrastructure to support world-class AI. For example, its tech giants like Huawei, Alibaba and startups like Cambricon can now produce GPUs comparable to what Nvidia was selling about 3 - 4 years ago — and closing. And with about 150 small modular reactors to be completed by 2035, as well as the world’s two biggest hydroelectric dams by far — the Three Gorges Dam and the 4-times larger Medog Hydropower Station on the Yarlung Tsangpo River — China is readying the energy piece as well.

Breaking the Bamboo Ceiling

The race for talent is also about more than simply hiring large numbers of Asians. It’s also about the quality of the jobs. Twenty years ago, leadership coach Jane Hyun’s 2005 self-help book popularized the term “bamboo ceiling,” which described how the phenomenon in which Asian Americans are unable to attain promotions past a certain point in the workplace.

In the tech world, Asian Americans have accounted for about 20% of the total workforce but until recently have only made up 10% of anything resembling a leadership position like manager, executive, or senior official. Unless we actually believe that Asian Americans are uniquely unqualified for positions of leadership, it’s hard to describe that bamboo ceiling as anything other than systematic bias.

But the need for AI workers is turning that bias on its head. As the Wall Street Journal notes, “People with AI experience are being promoted to management roles roughly twice as fast as their counterparts in other technology fields. They’re jumping the ladder as a result of their skills and impact instead of their years on the job.”

Frankly, these companies are too focused on the endgame of winning the AI race to let a distraction like racial stereotypes or xenophobia get in the way of hiring and promoting the brightest AI minds they can find.

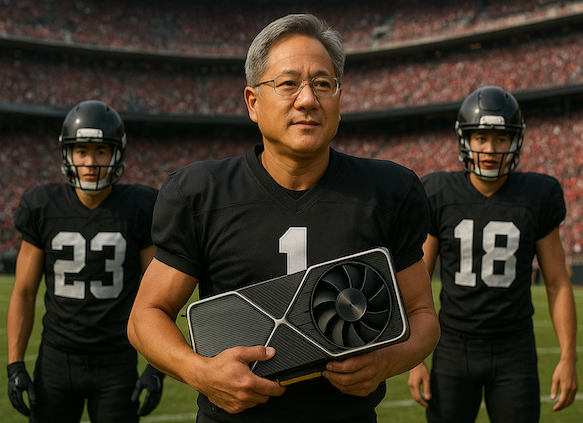

In fact, many of the top semiconductor businesses in the US — those making the actual hardware needed for AI — are led by Asian American CEOs: Taiwanese-born Jensen Huang at Nvidia and Lisa Su at AMD, Malaysian-born Lip Bu Tan at Intel and Hock Tan at Broadcom, and Indian-born Sanjay Nehrota at Micron. And the trend doesn’t seem to be slowing down.

To give you a sense of how things have changed: Think of the most famous tech CEOs in history.

There’s a chance that you’re imagining Steve Jobs pacing the stage of a full auditorium, clad in a black turtle neck and acid washed jeans. We remember his showmanship more than anything else. But in the AI race, anything short of a savant-like understanding of AI simply isn’t good enough. In other words, this is a matter of style over substance.

And many of those with that understanding are Asian.

Here’s a real sign of the times when it comes to Asian Americans’ footing in the industry: we’re seeing racism in our favor rather than against us for a change.

In March Google paid $28 million to settle a lawsuit claiming that it was favoring Whites and Asians when it came to hiring and salary.

Obviously racism is nothing to celebrate. But it’s certainly striking that an historically marginalized group like Asian Americans could be at the receiving end of preferential treatment.

The Downside

Every action, of course, has an equal but opposite reaction.

While many Asian Americans are benefitting from AI advancement due to the above reasons, we are also largely the ones who will be paying the price.

A rise in AI means less of a need for the workers currently paid to do many of the software development functions AI is set to replace with AI coding agents and development software.

One of the most vulnerable positions is that of software coders and developers. And it happens to be a profession that’s about 26% or more Asian American.

There is some sad irony in all of this. The phrase “learn to code” was employed so much during the 2010s that it’s become a cliche if not even a meme at this point. It was used to encourage those in jobs that are becoming obsolete to develop a new set of skills in order to pivot careers and save their livelihoods. It’s been thrown around as a solution for coal miners who are increasingly finding themselves in need of jobs as the world moves to cleaner energy sources.

As then-presidential candidate Joe Biden declared in 2019, "Anybody who can go down 300 to 3,000 feet in a mine, sure in hell can learn to program as well.”

And yet, just years later, it’s the programmers — those once praised for being forward thinking — who may now need to learn a new skillset as their own jobs become obsolete.

That said, a transition from coal mining to computer programming may be a bit more of a leap than the move from computing technology 1.0 to 2.0 which many Asian Americans are about to be making. It may take about 6-7 years for the most adaptable members of the current software coding workforce collectively to make the transition.

AI’s likelihood of displacing Asian Americans in professions outside of the tech world is just as great, if not greater.

Working class Asian Americans, many of whom are not proficient in English, hold jobs like food delivery, trucking, manicurist, and Uber/Lyft driving. AI is already threatening jobs like these with the development of driverless cars and drones to deliver food to one’s doorstep. Self- checkouts at grocery stores are putting grocery baggers out of a job.

Then there’s the matter of gentrification and displacement of AAPI neighborhoods.

The San Francisco Bay area has one of the highest concentrations of Asian Americans in the country. Roughly 35% of San Francisco’s residents identify as AAPI. The number is closer to 60% in some neighborhoods.

This has historical roots: In the mid-1800s, Chinese immigrants flocked there as a result of the gold rush and railroad construction jobs. Family reunification and other factors associated with the loosening of immigration restrictions throughout the years, including the locations of Stanford University and UC Berkeley have continued to make the area an AAPI hub.

But over the past couple of decades wealthy tech executives, whether they happen to be AAPI or not, have been buying up property in Silicon Valley and the surrounding area. As a result, many lower and middle class AAPI communities are being priced out.

It’s true that many of those pricing them out may themselves be Asian, a reminder of the importance of intersectionalist: real solidarity in a community should take both culture and class differences into account.

The Bottom Line

Culture can be a funny thing.

Many of the Asian Americans who will help win the AI race and take technology to a place we could never imagine are, well, still Asians without the “American” modifier. Some may choose to remain in the East, either out of national loyalty or simply based on the best offer.

What we do know is that Asian Americans are in the driver seat of American society in a way that we’ve never been before. Even those of us with a blank slate of knowledge when it comes to AI will benefit from those who look like us finally attaining positions of power.

Greater visibility through wealth and stature achieved by our involvement developing AI could very well open a whole new world, one in which AAPI representation on screen is no longer a scarcity. Or where US textbooks contain the images of Asian Americans to a degree that other more privileged groups have long enjoyed in this country.

In some ways, it doesn’t even matter what country technically wins the AI race. Asian Americans are already winning.

Asia appears to have developed monopolies in training talent capable of developing world-class AI technology.

This is due at least partially to the dense populations of those countries, and therefore raw numbers of qualified candidates that they’re able to produce. There are between 600,000 and 700,000 graduates in STEM fields in the US each year. China and India, on the other hand, produce 4 million and 2.6 million STEM graduates a year, respectively.

And it’s not just raw numbers but percentages as well. About 20% of US grads are in STEM. In China, that number is 30-35%.

Former presidential hopeful and current Ohio gubernatorial frontrunner Vivek Ramaswamy made headlines for posing a theory on Twitter late last year about why that is:

The reason top tech companies often hire foreign-born & first-generation engineers over “native” Americans isn’t because of an innate American IQ deficit (a lazy & wrong explanation). A key part of it comes down to the c-word: culture.

The cultural difference, in Ramaswamy’s view, is that Asians value nerdiness over coolness. They put a premium on, say, mathletes while the US gives more social status to the prom queen or football quarterback.

Whether or not you agree with Ramaswamy’s underlying diagnosis for Asian supremacy in producing STEM talent, it is undeniable that countries like China and India are simply producing more students and recent graduates with the skills that AI software companies need.

One alternative explanation — or perhaps, a direct result of that cultural difference — is explained by the sheer number of schools in Asia that offer a STEM education.

Ramaswamy also caught flack from members of his own party when it came to his solution, aside from changing the culture: granting more H-1B visas to those who have the skills.

But even those in his own Republican party — which is known for its hardline anti-immigration stance — may have come to the conclusion by now that there’s virtually no way around granting entry to a greater number of foreigners with the skills our AI companies require.

President Trump himself appears to have reached that conclusion. After months of threatening to revoke the visas of Chinese students, he’s struck a deal with China to admit 600,000 Chinese students to the US over the next two years.

This is a win for Asian Americans.

The move has angered members of Trump’s own base, like Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, celebrated by the MAGA base by elevating xenophobia to operatic scales.

And, yet, her concerns are likely born out of the same reasons that Asian Americans should be celebrating this news: the admittance of more Asian students will be a boon to Asian American culture. It’s likely to breed more Asian restaurants, entertainment and cultural districts.

This is just one way in which the rise of AI is a win for the AAPI community.

The Missing Pieces

If China is leaps and bounds ahead of the US in terms of talent, one might wonder why they haven’t gone full Usain Bolt and pulled ahead in the AI race already.

It’s because a football team that simply consists of Patrick Mahomes standing alone in the middle of a field is no football team. Talent needs to go hand in hand with the other moving parts required to fabricate the millions of high-powered, high-bandwidth graphic processing units (GPUs) to fill hundreds of giant data centers.

When it comes to producing that type of design and fabrication technology — developed painstakingly over the past 70 years of the computer age — China simply hasn’t been in the game long enough to match the US and its close allies like Taiwan, S. Korea, Japan and the Netherlands.

Their capabilities may be good, but at this level, good isn’t…well, good enough. It needs to be great —nay, perfect.

Any Breaking Bad fan surely remembers chemist-turned-drug kingpink Walter White’s fixation on the purity of the crystal meth he’s making: “You produce a meth that's 70% pure, if you're lucky. What I produce is 99.1% pure,” he says to his competitor. “Yours is just some tepid, off-brand, generic cola. What I'm making is classic Coke."

When it comes to the ability to churn out GPUs, the US and its allies are currently the Coke to China’s generic cola, although theirs is probably closer to 40% “pure” than 70%. In meth terms, to keep going with this Breaking Bad analogy: it can still get you high, you just need to buy 2-3x more of it. Which is to say that while China is nipping at our heels in terms of developing AI models, their ability to make the hardware to power them is perhaps three to five years behind. And given the pace at which the world is addicting to AI, those years may as well be dog years.

Still, China is catching up with the manufacturing hardware and infrastructure to support world-class AI. For example, its tech giants like Huawei, Alibaba and startups like Cambricon can now produce GPUs comparable to what Nvidia was selling about 3 - 4 years ago — and closing. And with about 150 small modular reactors to be completed by 2035, as well as the world’s two biggest hydroelectric dams by far — the Three Gorges Dam and the 4-times larger Medog Hydropower Station on the Yarlung Tsangpo River — China is readying the energy piece as well.

Breaking the Bamboo Ceiling

The race for talent is also about more than simply hiring large numbers of Asians. It’s also about the quality of the jobs. Twenty years ago, leadership coach Jane Hyun’s 2005 self-help book popularized the term “bamboo ceiling,” which described how the phenomenon in which Asian Americans are unable to attain promotions past a certain point in the workplace.

In the tech world, Asian Americans have accounted for about 20% of the total workforce but until recently have only made up 10% of anything resembling a leadership position like manager, executive, or senior official. Unless we actually believe that Asian Americans are uniquely unqualified for positions of leadership, it’s hard to describe that bamboo ceiling as anything other than systematic bias.

But the need for AI workers is turning that bias on its head. As the Wall Street Journal notes, “People with AI experience are being promoted to management roles roughly twice as fast as their counterparts in other technology fields. They’re jumping the ladder as a result of their skills and impact instead of their years on the job.”

Frankly, these companies are too focused on the endgame of winning the AI race to let a distraction like racial stereotypes or xenophobia get in the way of hiring and promoting the brightest AI minds they can find.

In fact, many of the top semiconductor businesses in the US — those making the actual hardware needed for AI — are led by Asian American CEOs: Taiwanese-born Jensen Huang at Nvidia and Lisa Su at AMD, Malaysian-born Lip Bu Tan at Intel and Hock Tan at Broadcom, and Indian-born Sanjay Nehrota at Micron. And the trend doesn’t seem to be slowing down.

To give you a sense of how things have changed: Think of the most famous tech CEOs in history.

There’s a chance that you’re imagining Steve Jobs pacing the stage of a full auditorium, clad in a black turtle neck and acid washed jeans. We remember his showmanship more than anything else. But in the AI race, anything short of a savant-like understanding of AI simply isn’t good enough. In other words, this is a matter of style over substance.

And many of those with that understanding are Asian.

Here’s a real sign of the times when it comes to Asian Americans’ footing in the industry: we’re seeing racism in our favor rather than against us for a change.

In March Google paid $28 million to settle a lawsuit claiming that it was favoring Whites and Asians when it came to hiring and salary.

Obviously racism is nothing to celebrate. But it’s certainly striking that an historically marginalized group like Asian Americans could be at the receiving end of preferential treatment.

The Downside

Every action, of course, has an equal but opposite reaction.

While many Asian Americans are benefitting from AI advancement due to the above reasons, we are also largely the ones who will be paying the price.

A rise in AI means less of a need for the workers currently paid to do many of the software development functions AI is set to replace with AI coding agents and development software.

One of the most vulnerable positions is that of software coders and developers. And it happens to be a profession that’s about 26% or more Asian American.

There is some sad irony in all of this. The phrase “learn to code” was employed so much during the 2010s that it’s become a cliche if not even a meme at this point. It was used to encourage those in jobs that are becoming obsolete to develop a new set of skills in order to pivot careers and save their livelihoods. It’s been thrown around as a solution for coal miners who are increasingly finding themselves in need of jobs as the world moves to cleaner energy sources.

As then-presidential candidate Joe Biden declared in 2019, "Anybody who can go down 300 to 3,000 feet in a mine, sure in hell can learn to program as well.”

And yet, just years later, it’s the programmers — those once praised for being forward thinking — who may now need to learn a new skillset as their own jobs become obsolete.

That said, a transition from coal mining to computer programming may be a bit more of a leap than the move from computing technology 1.0 to 2.0 which many Asian Americans are about to be making. It may take about 6-7 years for the most adaptable members of the current software coding workforce collectively to make the transition.

AI’s likelihood of displacing Asian Americans in professions outside of the tech world is just as great, if not greater.

Working class Asian Americans, many of whom are not proficient in English, hold jobs like food delivery, trucking, manicurist, and Uber/Lyft driving. AI is already threatening jobs like these with the development of driverless cars and drones to deliver food to one’s doorstep. Self- checkouts at grocery stores are putting grocery baggers out of a job.

Then there’s the matter of gentrification and displacement of AAPI neighborhoods.

The San Francisco Bay area has one of the highest concentrations of Asian Americans in the country. Roughly 35% of San Francisco’s residents identify as AAPI. The number is closer to 60% in some neighborhoods.

This has historical roots: In the mid-1800s, Chinese immigrants flocked there as a result of the gold rush and railroad construction jobs. Family reunification and other factors associated with the loosening of immigration restrictions throughout the years, including the locations of Stanford University and UC Berkeley have continued to make the area an AAPI hub.

But over the past couple of decades wealthy tech executives, whether they happen to be AAPI or not, have been buying up property in Silicon Valley and the surrounding area. As a result, many lower and middle class AAPI communities are being priced out.

It’s true that many of those pricing them out may themselves be Asian, a reminder of the importance of intersectionalist: real solidarity in a community should take both culture and class differences into account.

The Bottom Line

Culture can be a funny thing.

Many of the Asian Americans who will help win the AI race and take technology to a place we could never imagine are, well, still Asians without the “American” modifier. Some may choose to remain in the East, either out of national loyalty or simply based on the best offer.

What we do know is that Asian Americans are in the driver seat of American society in a way that we’ve never been before. Even those of us with a blank slate of knowledge when it comes to AI will benefit from those who look like us finally attaining positions of power.

Greater visibility through wealth and stature achieved by our involvement developing AI could very well open a whole new world, one in which AAPI representation on screen is no longer a scarcity. Or where US textbooks contain the images of Asian Americans to a degree that other more privileged groups have long enjoyed in this country.

In some ways, it doesn’t even matter what country technically wins the AI race. Asian Americans are already winning.

Asian Americans are in the driver seat of American society in a way that we’ve never been before. Even those of us with a blank slate of knowledge when it comes to AI will benefit from those who look like us finally attaining positions of power.

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang is one of a gorwing number of Asian Americans in a leadership position thanks to the AI boom.

Asian American Success Stories

- The 130 Most Inspiring Asian Americans of All Time

- 12 Most Brilliant Asian Americans

- Greatest Asian American War Heroes

- Asian American Digital Pioneers

- New Asian American Imagemakers

- Asian American Innovators

- The 20 Most Inspiring Asian Sports Stars

- 5 Most Daring Asian Americans

- Surprising Superstars

- TV’s Hottest Asians

- 100 Greatest Asian American Entrepreneurs

- Asian American Wonder Women

- Greatest Asian American Rags-to-Riches Stories

- Notable Asian American Professionals