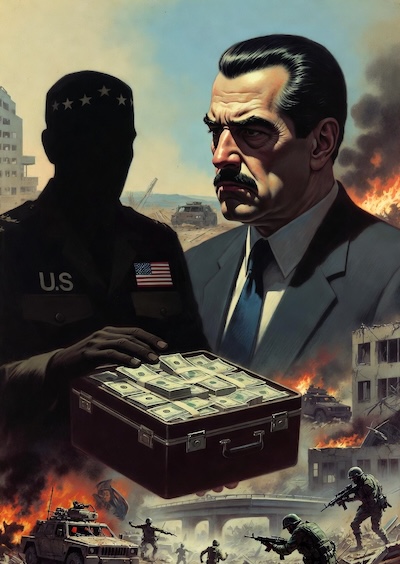

Simple Math Should Discourage Superpower Imperialism

By Tom Kagy | 14 Jan, 2026

The economics of imposing foreign rule—as well as military history—should discourage any rational leader from entertaining the ambition of seeking control of a small poor neighbor.

A modern superpower attempting to directly control a 3rd-world nation of 30 million people is doomed from the start — if not by morality — then by simple arithmetic.

The economic burden of occupation, the military requirements of suppressing resistance, and the historical record of great powers bleeding themselves dry in foreign quagmires leads to the conclusion that only a foolish superpower would attempt direct rule over any unwilling population.

This conclusion doesn't involve sentimentality about sovereignty or a romantic belief in national self‑determination. It’s the cold, hard math of manpower, logistics, budgets, and political sustainability. Empires didn’t collapse because they lost their appetite for domination; they collapsed because domination became too expensive.

The Occupation Equation

Start with the simplest variable: population. A country of, say, 30 million people (about the size of Venezuela) has its own institutions, networks and social cohesion. To impose direct rule over such a population, especially one that is hostile or resentful, requires a massive security presence.

Counterinsurgency doctrine offers a rule of thumb: you need roughly 20 to 25 security personnel per 1,000 inhabitants to maintain control in a hostile environment. That means policing, intelligence, checkpoints, patrols, and the constant projection of force.

Applying that ratio to 30 million people requires an occupation force of 600,000 to 750,000 troops — or about 60% of the entire US military. That baseline doesn’t include support personnel, logistics, medical units, air support, or the civilian administrators needed to run the machinery of governance. Add those and the total easily surpasses one million personnel.

No modern superpower, including the US, has the political will, the manpower, or the budget to sustain such a deployment indefinitely. Even the largest standing armies in the world would buckle under the weight of maintaining that many troops abroad.

Budgetary Black Hole

Modern military deployments are staggeringly expensive. During the height of the Iraq War, the United States spent roughly $10 billion per month. That was for a country of about 25 million people, with a troop presence far smaller than called for by counterinsurgency doctrinel.

A full‑scale occupation of a 30‑million‑person nation—especially one resisting foreign rule—would dwarf those costs. Even a conservative estimate would place the annual price tag in the hundreds of billions of dollars. And that’s before factoring in reconstruction, infrastructure, bribery networks to maintain local compliance, and the inevitable corruption that accompanies any large‑scale foreign intervention.

Superpowers have domestic constituencies, budget constraints, and political cycles. Voters tolerate foreign adventures only when they are cheap, quick, and victorious. A multi‑year occupation that drains the treasury and produces a steady stream of casualties is political poison.

The math is simple: the cost of occupation exceeds the value of whatever strategic or economic benefit the superpower hopes to extract. Colonialism made sense in the 19th century because the extraction of resources was cheap and military technology gave empires overwhelming dominance. Today, extraction is expensive, resistance is technologically empowered, and global markets make direct control unnecessary.

Logistics of Resistance

Even if a superpower were willing to pay the financial cost, it would still face the logistical nightmare of suppressing a population that wants it out. Modern insurgencies don't require large armies, only small groups with local knowledge, access to cheap homemade explosives, and the ability to blend into the civilian population.

A hostile population of 30 million provides an almost infinite reservoir of potential fighters, informants, saboteurs, and sympathizers. Even if only 1 percent of the population actively resists, that’s 300,000 insurgents—more than enough to tie down a superpower for decades.

History shows that insurgencies don't need to win battles; they only need to avoid losing. T heir goal is to make occupation too costly, too bloody, and too politically toxic for the occupier to sustain. From Afghanistan to Vietnam to Algeria, the pattern is consistent: the superpower wins every major battle and always loses the war.

Historical Ledger of Failure

The 20th and 21st centuries are littered with examples of powerful nations attempting to impose direct control over large populations—and failing spectacularly.

The Soviet Union in Afghanistan deployed over 100,000 troops and still couldn't pacify a country with a population smaller than 20 million at the time. The United States in Vietnam deployed more than 500,000 troops and still couldn't impose its preferred political order. France in Algeria, Britain in Palestine, Portugal in Angola—the list goes on.

In each case, the superpower had overwhelming military superiority. In each case, the superpower could win tactical engagements at will. And in each case, the superpower eventually withdrew, not because it was defeated militarily, but because the cost of staying exceeded the benefit.

So the lesson isn't ideological but mathematical. The ratio of force required to control a large, hostile population is simply too high. The cost of maintaining that force is too great. The political consequences of sustaining that cost are too severe.

Modern Twist: Technology Favors the Defenders

Some might argue that modern surveillance, drones, and precision weapons make occupation easier. In reality, they make it harder. Technology has democratized resistance. Cheap drones, encrypted communication, improvised explosives, and social media coordination give insurgents tools that can wreak havoc and generate casualties—without constraints.

Meanwhile, the superpower must operate under the constraints of international law, global media scrutiny, and domestic political pressure. Every civilian casualty becomes a viral video. Every misstep becomes a diplomatic crisis. The occupier must be perfect; the insurgent only needs to be persistent.

Opportunity Cost of Imperial Fantasy

Even if a superpower could theoretically muster the resources to occupy a nation of 30 million, doing so would require diverting those resources from other priorities: economic development, technological innovation, alliances, and domestic stability. In a world of great‑power competition, wasting trillions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of troops on a colonial project is strategic suicide.

Modern power is measured not by how many people a nation can subjugate, but by how effectively it can project influence without direct control. Soft power, economic leverage, and diplomatic networks achieve what colonial armies once did—at a fraction of the cost.

Final Calculation

Add up the numbers—troop requirements, financial cost, political risk, logistical complexity, and historical precedent—for the only possible conclusion: seeking direct control over a nation of 30 million people is a demonstration not of strength but of historic ignorance and strategic incompetence.

A rational superpower seeks influence, not ownership. It shapes outcomes through alliances, incentives, and economic ties, not through bayonets and occupation zones. The age of empire is over not because the world became more moral, but because the math stopped working.

Any superpower leader that ignores that math is super-powerfully stupid.

(Image by Gemini)

Asian American Success Stories

- The 130 Most Inspiring Asian Americans of All Time

- 12 Most Brilliant Asian Americans

- Greatest Asian American War Heroes

- Asian American Digital Pioneers

- New Asian American Imagemakers

- Asian American Innovators

- The 20 Most Inspiring Asian Sports Stars

- 5 Most Daring Asian Americans

- Surprising Superstars

- TV’s Hottest Asians

- 100 Greatest Asian American Entrepreneurs

- Asian American Wonder Women

- Greatest Asian American Rags-to-Riches Stories

- Notable Asian American Professionals