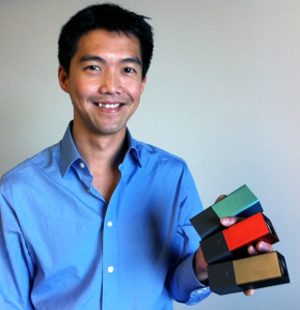

Ren Ng's Lytro Camera Debuts Mostly to Raves

By wchung | 03 Feb, 2026

Ren Ng's Lytro has begun shipping to those who pre-ordered them at the end of last year.

When Ren Ng succeeded in building a working prototype of the Lytro camera last year, it was hailed as the biggest technological advance in photography since the invention of the camera itself. Now that the first pre-ordered units have begun shipping on March 1, consumers are deciding for themselves whether the Lytro lives up to the claim.

The 16-gig model for $499 and an 8-gig model for $399 may seem pricey for a device that looks blocky, bulky and simple like a small child’s colorful plastic toy rather than a technological marvel. Nothing on the surface of the Lytro camera suggests the ability to do much other than point and click. That’s exactly the point.

Ng’s revolutionary lightfield technology captures all the available light data, including the amount and angle of light from every point of a scene. The key is a glass layer patterned with 11 million tiny angled lenses placed atop a conventional digital camera sensor. The tiny lenses allow the sensor to record not only RGB color data but the precise angle of each pixel-producing ray. That angular pixel data allows Lytro’s software to apply an algorithm to generate an images focused to any focal length. In practical terms, it means that the user taps or clicks on any face or object on the image and bring it into focus.

The cost to capturing all that angular data is a loss of resolution. Each focused image from the Lytro can display about 640,000 pixels whereas a typical $200 digital camera, or even a smartphone camera, can display from about two to eight million pixels. Ng discounts the value of those lost pixels because most images are sampled down drastically before they are used. What’s more, the optics of most inexpensive digital cameras don’t really allow the capture of enough light information to support many millions of significant pixels, many claimed pixels being merely extrapolations.

Lytro’s real significance is the use of angular data to make pixels truly dynamic, opening the door to an entirely new way of combining the data processing capabilities of a computer with the light-capturing capabilities of a camera.

There’s no need to manipulate the lenses to focus on a particular subject or plane; that’s done later by manipulating the captured data from the comfort of one’s own Mac (the software currently works only on Macs though a Windows version is promised). At the moment of capture the user only has to do what only a human being can do — decide what part of the scene he wants to record. The result of that shutter click is what Ng calls “a living picture” that can be focused and refocused on whatever subject is desired at any given moment.

So far the reviews has been positive from the few users who have gotten their hands on a Lytro. A few have complained that it doesn’t capture images well in low-light conditions and that in very bright light — the optimal condition for lightfield technology — the viewfinder is obscured by glare. Some have suggested that the technology will be more useful when it becomes advanced enough to compress into a smartphone. Not everyone agrees that the camera will be an industry game-changer, mainly because the device, as simple as it appears on the outside, has its own learning curve for taking pictures that exploit the Lytro’s infinite-focus capability. Point it at a scene of mostly faraway objects and it’s hard to see much difference between one focal point and another.

But Lytro’s prospects as a pioneering consumer electronics firm that’s likely to stick around to tap the niche seems fairly secure. Ng has already raised $50 million from respected venture capitalists like like Charles Chi of Greylock Partners, Patrick Chung of NEA and Ben Horowitz of Andreessen Horowitz. Its board of advisers is well stacked with two Nobel laureates — Stanford physics professor Douglas Osheroff and physicist Arno Penzias — Intuit cofounder Scott Cook, Dolby Labs Chairman Peter Gotcher, VMware cofounder Diane Greene and Sling Media cofounder Blake Krikorian.

The idea for a camera that records light fields rather than a two-dimensional collection of dead pixels came to Ng when he was studying light fields as a Stanford PhD student. The difficulty of focusing his new digital SLR on his active 5-year-old daughter inspired Ng to consider the practicality of a cameras that can record all the light field data needed to allow an image to be resolved to the desired focal plane after the photo is taken. Such a camera would eliminate even the need to focus a picture.

Ng’s investigation into the feasibility of a practical light-field (or plenoptics) camera grew into his 200-page PhD dissertation titled Digital Light Field Photography. Submitted in July 2006, the dissertation was intriguing enough win the ACM Doctoral Dissertation Award for best thesis in computer science and engineering. It also won Stanford University’s Arthur Samuel Award for Best Ph.D. Dissertation.

The dissertation’s biggest fan proved to be Ng himself. He decided the work would form the basis for a venture to build and market a consumer plenoptics camera. On the strength of the dissertation, Ng attracted $80 million in venture funding for Lytro. The company has already put prototype plenoptics cameras into the hands of a number of testers who have been capturing light-field images that probably represent the future of digital photography. By clicking on any point of an image, a viewer can refocus the image onto the focal plane of any pictured object. Ng began taking pre-orders for the camera in time for the 2011 holiday season.

“The megapixel war in conventional cameras has been a total myth,” Ng says. “It’s taking us all in the wrong direction. Once a picture goes online, you’re throwing away 95 to 98 percent of those pixels. Light fields can use all that resolution, those megapixels, harness them, and drive them into the future.”

Instead of capturing superflous megapixels of data from a sensor recording a scene through a single lens, the Lytro plenoptics camera captures data from an array of small lenses positioned at various angles above the sensor. That angular information associated with each individual pixel can be used to extrapolate an image that is focused on a subject’s face, for example, instead of the roses in front of it, thereby giving viewers access to a “living picture”.

“There’s something about light field photography that’s just magical,” Ng says. “It very much is photography as we’ve known it. It’s what we’ve always seen through cameras — we just had to fix it. We’ve had these kind of pictures floating on our retinas, for as long as we’ve been humans.”

Each image data file comes packaged with HTML5, Flash and other native app technologies needed to perform the necessary calculations to derive the pixels as they appear when an image is focused on a viewer’s desired focal plane, making each image as accessible to a viewer as any digital image except with the added versatility.

Ren Ng, 31, is an avid rock climber. He holds a Ph.D. in computer science and a B.S. in mathematical and computational science from Stanford University.

Ren Ng's Lytro cameras began shipping in early March to those who had begun pre-ordering the revolutionary lightfield cameras in December of 2011.

Articles

Asian American Success Stories

- The 130 Most Inspiring Asian Americans of All Time

- 12 Most Brilliant Asian Americans

- Greatest Asian American War Heroes

- Asian American Digital Pioneers

- New Asian American Imagemakers

- Asian American Innovators

- The 20 Most Inspiring Asian Sports Stars

- 5 Most Daring Asian Americans

- Surprising Superstars

- TV’s Hottest Asians

- 100 Greatest Asian American Entrepreneurs

- Asian American Wonder Women

- Greatest Asian American Rags-to-Riches Stories

- Notable Asian American Professionals